- Home

- Amanda Foody

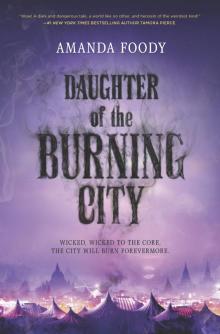

Daughter of the Burning City Page 6

Daughter of the Burning City Read online

Page 6

Because I’ve been training with Villiam and learning about how Gomorrah works for years, I also know that moving the entire city is no easy feat to accomplish in several days, let alone a few hours. He genuinely does not have time for me.

“Send my apologies to our family. Tell them I’m thinking of them. I wish I could be there to help them in person. This is...such a tragedy,” he says, tears glistening in his eyes. “And promise me you’ll return when the commotion has died down.”

The commotion won’t disappear for several days, not until we reach the next city. It’s hard to think that far into the future. It’s hard to picture anything except the night ahead of me, of packing up the stage where Gill died, of burying him without a coffin, without a ceremony. It’s impossible to think beyond saying goodbye.

Nevertheless, I mutter, “I promise.”

CHAPTER FOUR

The Gomorrah Festival does not travel like other circuses, groups of wanderers, bands of musicians, thieves or markets, because it is all of those at the same time. If someone stood at the peak of the Winding Pass—the stony, barren mountains we are crossing to reach the city of Cartona—it would appear as if an entire burning city were on the move beneath them. Due to the suddenness of our departure, tents are still raised and wheeled on platforms, parties continue in the Downhill as the sun begins to rise and the white torches glimmer within the haze of smoke. It goes on for miles, with a population of over ten thousand inhabitants. Our nickname is “The Wandering City.”

If that same person had watched the Gomorrah Festival travel before, they would also realize that its atmosphere feels different this morning. More subdued and downcast. There’s less music, laughing and cheering since the Fricians kicked us out.

Or maybe the morning wind is cooler than usual, and it’s just a chill. Gomorrah is older than anyone can remember and unlikely to be intimidated by the actions of a single Up-Mountain city-state.

Perhaps I am the only one in Gomorrah feeling the chill. Perhaps, after Gill’s death, the music, laughing and cheering is quieter only to me.

Apart from Tree, who prefers to walk on his own, my family sleeps in two separate caravans when we travel—one for Crown, Gill, Unu and Du and Blister, and one for the rest of us. I sleep between Nicoleta and Venera. Hawk’s feet are across from mine and sometimes kick me during the day while we rest. The caravan is packed full of trunks, the floor covered in blankets and the ground in between littered with popcorn kernels and peanut shells.

I sit up and stare out the window at the Winding Pass peaks jutting into the sky, mere silhouettes through Gomorrah’s smoke. The sun has risen, barely. Gomorrah is beginning to go to bed, and I have yet to fall asleep. The memories of Gill’s corpse and his brief burial a few hours ago continue to haunt me. Even though I’ve washed my hands over and over, removing every last trace of blood, I wipe them on my bedsheets once, twice, three times.

I replay my last conversation with Gill over in my mind. I was a jerk. Not only yesterday, the day he died, but the day before, and before, and before. I could’ve listened to his advice more often. Read the books he suggested. Made an effort to spend time with him, instead of avoiding his lectures.

I want to sleep until reality feels more like a dream. I want to never wake up.

But I have business to attend to and others to look after. Jiafu will still be awake in the Downhill. Even though it’s dawn and no longer safe to venture outside, I’ll have to take my chances for now. At least this errand will keep me distracted.

I slept in my regular clothes last night, so I crawl past Hawk and creak open the door. Then I jump out of the moving caravan into the knee-high grass of the Winding Pass.

Gomorrah can be more difficult to navigate while it’s moving, but I’ve explored the Downhill once before during the day, when the nicest people of the Downhill—which is not saying very much—are asleep and the rest of the crooks are awake. In the Downhill, no one cares that I’m Villiam’s adopted daughter. Actually, they’d probably love to skin me because of it. No one there is a star performer, a great attraction or seemingly special at all. In Gomorrah, everyone might be treated equally, but, in the end, money divides the affluent from the rest. If Villiam wasn’t paying for my family’s space, we’d barely be affording the Uphill ourselves.

It takes me ten minutes to walk to where the Uphill intersects with the Downhill. There’s a fifty-meter gap between those two sections of caravans, and as I trudge across the small, open field, I feel eyes peering at me from ahead. People are watching me, wondering why an Uphill girl would visit them at this hour.

The wood of the caravans here rots from years of rain, with holes along the walls just large enough to toss out the contents of an ashtray or for someone to covertly slip a delivery in the gap beneath a windowsill. The ribs of horses, mules and the occasional more exotic elephants who pull the caravans are more pronounced. Their eyes burn red, and their dirty coats swarm with clouds of fleas. I worry that if I get too close, they might mistake me for the meal their owners forgot to feed them.

Thankfully, Jiafu doesn’t live deep within the Downhill, and I make it there without becoming a horse’s breakfast. The cramped caravan he calls home is striped purple and black, with no sign or indication of what a visitor might find inside. All of his clients already know who he is and where to find him—he doesn’t need advertisements.

I knock on the dull black door and walk to keep up with it. No response. After thirty seconds of more knocking—and a man poking his head out of a nearby caravan, telling me to piss off—Jiafu answers. He grimaces when he sees me and rubs his temples, one of which has a deep scar that snakes down to his chin.

“What do you want?” he asks. His shadow dances on the grass below him, twisting into almost gruesome positions, as if trying to tear itself away from the body casting it.

“You weren’t waiting for me last night,” I say. “After the show.”

“There were officials about. I needed to head back home and protect my merchandise.”

“I want the money now. I want my cut.”

“Too bad. I haven’t sold it yet. I don’t got your cut. Now run away, princess.”

“Sold what yet?” I say, loudly and dramatically. “Oh, you mean the priceless ring of Count...Pomp-di-something from Frice? That’s worth a fortune?”

The man who told me to piss off earlier pokes his head outside again. As do a few others. I have their attention.

Jiafu narrows his eyes and then he yanks me by my tunic and hoists me into his caravan. Inside, there are five times as many crates as in my own, with just enough floor space for a mattress in the corner. Everything reeks of burnt coffee and feet.

“You think I had a chance to sell the ring?” he hisses. “We just left Frice.”

“I didn’t expect Kahina to have to travel again so soon. I want the money to get her medicine as soon as we get to Cartona.” Packing and traveling isn’t easy on her, especially in this part of the Up-Mountains, where the roads are unpaved and hard on her bones. And now that Gill is...now that Gill is gone, ensuring Kahina stays healthy is more important to me than ever. I can’t lose anyone else.

He pauses. “There is another job. One of my men noticed this guy carrying a big purse of change. He’s at a bar now getting piss-drunk. If you could make an illusion, someone to mug him—”

“That’s not how it works,” I say, annoyed. I’ve had this conversation with Jiafu before.

“You said it takes a while to make an illusion, but I’ve been to several of your shows, and your act is different each time. You make it up on the spot.”

I rub my temples. “Yes, that type of illusion is improv. But you’re asking for a person. You’re asking for someone you can touch, hear and smell, someone real like Nicoleta and the others. They take me months.”

“Then get start

ed making one. Big, preferably good with a sword—”

“The answer is no.”

Even though I’ve technically made all of my illusions, I don’t really think of them that way. They’re their own persons. They’re my family. I created them to be the friends I never had.

I’m not exactly the most popular person in the Festival. Who would trust someone who has the power to deceive you in every manner?

He jabs his finger in my face. “Look, freak, that job wasn’t easy last night when you had the Count sitting in the front, and—”

I hold back my wince. “If you call me freak again, you’ll think maggots are eating out your insides.” I take three steps forward. Jiafu is several inches taller than me, but that doesn’t matter. I can make him look like an ant. I can make myself look like a giant.

He leans back. “Hey now, ’Rina, don’t be like that. We’re cousins, eh?”

Jiafu plays this card a lot. He comes from the Eastern Kingdoms of the Down-Mountains, like me, so he thinks we’re family. We’re not even friends.

“Don’t bother. I want my cut. I want my thirty percent. And I want it as soon as possible.”

He collapses onto the floor mattress and kicks his legs up on a crate. “There’s nothing I can tell you. I want to give you the money. Really, I want to. I want to reward all my friends.” I narrow my eyes. We’re. Not. Friends. “But I don’t have anything. I’ll sell it in Cartona. Then you get your cut.”

I sigh. This is about what I expected. Sure, Jiafu probably has some money hidden inside these crates that he could give me, but that would take a bit of coercion on my part. It would take an impressive illusion to make him cooperate. What would scare Jiafu? An enraged ex-mistress? A debt collector? I didn’t get enough sleep for my imagination to be at its best.

“Sorry, cousin,” Jiafu says.

“You’re not my family.”

“Would you prefer princess?” He lifts his left leg and points his calloused toe toward the door. “Come back after we’re settled in Cartona, and I have time for some business.”

“I will.” I try to make my voice sound forceful, intimidating, but I only sound broken. I plaster a smile on my face and push aside the thoughts of Kahina’s snaking sickness and of Gill. Then I mutter a goodbye and jump out of his caravan.

I’m not on my game.

Outside is the sound of millions of caravans moving and horses trotting. I walk past the smell of opium teas and a sign for what I’m sure is questionable goat curry.

Sleep will be impossible, so instead of making my way home, I head toward the center of the Uphill, toward a particular caravan decked out in fuchsia drapes and murals finger-painted by neighboring children. A sign on the door reads Fortune-Worker: Explore the Successes, Loves And Wonders That Await You.

I knock. It’s not as if she’s sleeping. In all the time I’ve known her, Kahina barely sleeps. She stays awake most of the day watering her herb garden and stringing necklaces and belts out of forgotten coins. And worrying about everyone’s futures. She should spend more time concerning herself with her own.

“I’m not done yet,” she calls from inside.

“No, it’s me,” I say.

A pause. There’s a rustle that sounds of coins tinkling together. Then she opens the door, a smile stretching across her face. “Sorina.” She holds out her hand to help me into the caravan.

The first thing I notice is the purple of her veins that spread from her fingertips up her forearm in a winding, swollen web. I freeze.

She laughs and switches hands. Her right one is normal and not yet infected. I grab it and climb into her caravan, eyeing her hesitantly. Other than the dark, snaking veins, she looks healthy. Which almost makes the sickness crueler, convincing you she’s fine until, very suddenly, she won’t be. The sickness will creep through her blood, snaking through her bloodstream into either her heart, lungs or brain—wherever it reaches first. The process can take years. From there, the disease progresses quickly, attacking the organ and deteriorating it cell by cell, until it can no longer function. No one knows how it spreads, but it’s common, both in the Up- and Down-Mountains.

Her long dreadlocks are pulled into a bun, full and beautiful. Her brown skin has its normal glow. Her ankle-length skirt and tunic fit her the same as always. Sometimes it’s easy to forget that she’s dying.

She occupies an entire medium-sized caravan to herself. Usually, that would be quite expensive, but since she has grown ill, a lot of her friends and neighbors have pulled their resources together to make her more comfortable. Kahina chose to use the extra space to add more volume to her herb and vegetable garden, many of which she makes into medicines or herbal teas. Unfortunately, none of them are rare enough to treat her own disease. The potted plants take up the majority of her home, and I brush a palm leaf out of my way as I crawl into her actual living space, which is mainly taken up by her bed, a drawer for fortune-work objects like crystals and cards, and a short table. The pots clack together as the caravan rides across the bumpy road.

Kahina lies back down on her bed and returns to the embroidery she was working on. With its red stitching and plain patchwork, it’s meant for a newborn boy. As the baby ages, the empty patches will be filled with cross-stitching depicting various life moments.

“Tya is going to have a boy in January,” Kahina says. “I figured I might as well start now.”

Kahina’s jynx-work allows her to glimpse into the future of individuals. She’s accurate the majority of the time, but I’ve witnessed a few occasions where she’s gotten a detail wrong. So it seems rash for her to make a blanket for a child that may still be born a girl. Especially because fortunes grow less certain the further into the future Kahina searches.

“You couldn’t wait a few more months to start?” I ask.

“I may not have a few more months.”

I pause before sitting down in the corner of her caravan. “You can’t talk like that,” I plead. “You can’t. I’m getting you medicine. The best quality there is. I’m not going to let anything happen...” My voice cracks. “Nothing is going to happen to you.” My head hurts from the build-up of pressure, and I steady my breathing to avoid crying. Damn it. I thought I could compose myself, but I am one unpleasant thought away from hysterics, no different than a few hours ago. I thought being in the comfort of Kahina’s caravan would help.

“You’re right,” Kahina says quickly. “I shouldn’t say things like that. Are you all right, Sorina?”

“Y-yes,” I say. But talking makes my breathing stagger, and then I can’t hold it back anymore. I cough out a sob, which turns into another and then another. There are no tears, of course, but my face reddens and my nose runs. I feel as though my entire heart has shattered.

“What has made this come on?” she asks, crawling to my side.

I bury my face into her shoulder and mumble something unintelligible.

“You’re really worrying me—”

“Gill’s dead. Someone killed him. Last night.”

I feel her whole body go rigid with shock. “What do you mean, someone killed him?”

I tell her the entire story, just like I told Villiam last night, and it’s no easier to share a second time. As I near the end, Kahina gets up to pour me a stone-cold mug of chamomile tea. “We were arguing when I last talked to him,” I choke. “I... I wasn’t kind.”

“Arguing about what?” Kahina asks.

“Nothing important,” I lie. She wouldn’t like to hear that I’ve been working with a Downhill thief to supply her medicine. I’ve been telling her that the Freak Show has been booming lately. I’m not certain if she buys this, but Kahina always said I don’t have to tell her anything I don’t want to. Before this, I’ve never had anything to conceal from her.

She presses me closer to her and hands me the t

ea. Then she runs her fingers through my hair, the way she used to when I was a child. “I’m so sorry, sweetbug. I wish I could’ve seen this coming.”

Kahina is unable to see the fortunes of my illusions because they aren’t entirely real.

But apparently they’re real enough to die.

I wish I could tell her about how worried I am about her, too. About how I feel the same anxiety, as if, even though my lungs are expanding, I’m not getting any air. And the feeling won’t go away. But Kahina hates it when I bring up her health. She hates to see how it affects me.

“It’s not fair,” I say. “It’s not fair that the Up-Mountainers get to storm our Festival and then call us the criminals. They get drunk, and they buy drugs, and they pay for all sorts of sins and call us the sinners for giving them the business they want.” I wipe my nose with the back of my hand.

“I don’t like to hear you talking like that,” Kahina says gently.

“What do you mean? It’s the truth. What they do isn’t right.”

“No, it isn’t right. But that doesn’t mean I like to hear my sweetbug saying ugly, angry things. Not my beautiful sweetbug. You’re allowed to be sad. Of course you can grieve. And anger is a stage of grief. But some never move beyond that, and I worry about you when you say such things.” She tugs at the ribbon of my mask until it slips off. “There. That feel better?”

Kahina always treats me like a child. She treats everyone like children, even people with more wrinkles and body aches than her. Her only child died at only two months old many, many years ago, yet she always said it was her destiny to be a mother, that every fortune-worker in Gomorrah told her that. So Kahina became a sort of mother to everyone in the Festival, quilting blankets, sending baskets of tea and keeping lucky coins for everyone she cares about.

King of Fools

King of Fools Ace of Shades (The Shadow Game Series)

Ace of Shades (The Shadow Game Series) King Of Fools (The Shadow Game series, Book 2)

King Of Fools (The Shadow Game series, Book 2) Ace of Shades_The Shadow Game Series

Ace of Shades_The Shadow Game Series Daughter of the Burning City

Daughter of the Burning City