- Home

- Amanda Foody

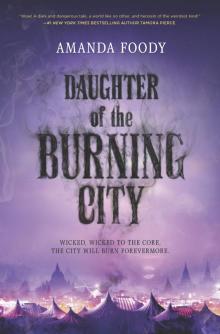

Daughter of the Burning City

Daughter of the Burning City Read online

A darkly irresistible new fantasy set in the infamous Gomorrah Festival, a traveling carnival of debauchery that caters to the strangest of dreams and desires

Sixteen-year-old Sorina has spent most of her life within the smoldering borders of the Gomorrah Festival. Yet even among the many unusual members of the traveling circus-city, Sorina stands apart as the only illusion-worker born in hundreds of years. This rare talent allows her to create illusions that others can see, feel and touch, with personalities all their own. Her creations are her family, and together they make up the cast of the Festival’s Freak Show.

But no matter how lifelike they may seem, her illusions are still just that—illusions, and not truly real. Or so she always believed...until one of them is murdered.

Desperate to protect her family, Sorina must track down the culprit and determine how they killed a person who doesn’t actually exist. Her search for answers leads her to the self-proclaimed gossip-worker Luca. Their investigation sends them through a haze of political turmoil and forbidden romance, and into the most sinister corners of the Festival. But as the killer continues murdering Sorina’s illusions one by one, she must unravel the horrifying truth before all her loved ones disappear.

Amanda Foody

Praise for Daughter of the Burning City

“Amanda Foody’s stunning debut is full of velvety language, intricate worldbuilding, and a story that treads the fine line of horror and fantasy. This is the kind of read that makes your spine shiver, and your heart beat faster.”

—Roshani Chokshi, New York Times bestselling author of The Star-Touched Queen

“Utterly original. Amanda Foody has a wicked imagination. If you enjoy your fantasy on the darker side, then you will love Gomorrah!”

—Stephanie Garber, New York Times bestselling author of Caraval

“I love the vivid, sumptuous world Amanda Foody has created: Sorina’s magic, her illusionary family and the Gomorrah Festival make for a wildly inventive mystery I won’t soon forget.”

—Virginia Boecker, author of The Witch Hunter series

Amanda Foody has always considered imagination to be our best attempt at magic. After spending her childhood longing to attend Hogwarts, she now loves to write about immersive settings and characters grappling with insurmountable destinies. She holds a Master of Accountancy degree from Villanova University and has a Bachelor of Arts in English literature from the College of William and Mary. Currently, she works as a tax accountant in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, surrounded by her many siblings and many books.

Daughter of the Burning City is her first novel. Her second, Ace of Shades, will follow in April 2018.

www.AmandaFoody.com

For my Quidditch team:

Ryan &

McKenna &

Parker &

Alex &

Connor &

Erica.

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Gill illustration

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Blister illustration

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Nicoleta illustration

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Venera illustration

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Hawk illustration

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Unu and Du illustration

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Crown illustration

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Tree illustration

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Luca illustration

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Acknowledgments

CHAPTER ONE

I peek from behind the tattered velvet curtains at the chattering audience, their mouths full of candied pineapple and kettle corn. With their pale faces flushed from excitement and the heat, they look as gullible as dandelions, much like the patrons in the past five cities. The Gomorrah Festival hasn’t been permitted to travel this far north in the Up-Mountains in over three years, and these people look like they’re attending the opera or the theater rather than our traveling carnival of debauchery.

The women wear frilly dresses in burnt golds and oranges, buckled to the point of suffocation, some with rosy-cheeked children bouncing on their laps, others with cleavage as high as their chins. The men have shoulder pads to seem broader, stilted loafers to seem taller and painted silver pocket watches to seem richer.

If buckles, stilts and paint are enough to hoodwink them, then they won’t notice that the eight “freaks” of my freak show are, in fact, only one.

Tonight’s mark, Count Pomp-di-pomp—or is it Count Pomp-von-Pompa?—smokes an expensive pipe in the second row, his mustache gleaming with leftover saffron honey from the pastry he had earlier. He’s sitting too close to the front, which won’t make it easy for Jiafu to steal the count’s ring.

That’s where I come in.

My job is to distract the audience so that Pomp-di-pomp doesn’t notice Jiafu’s shadow-work coaxing the sapphire ring off of his porky finger and dropping it onto the grass below.

A drum and fiddle play an entrancing Down-Mountain tune to quiet the audience’s chatter, and I let the curtain fall, blocking my view. The Gomorrah Festival Freak Show will soon begin.

This is my favorite part of the performance: the anticipation. The drumbeats pound erratically, as if dizzy from drinking several mugs of the Festival’s spiced wine. Everything sticks in this humid air: the aromas of carnival food, the gray smoke that shrouds Gomorrah like a cloak and the jittery intakes of breath from the audience, wondering whether the freak show will prove as gruesome as the sign outside promised:

The Gomorrah Festival Freak Show.

Walk the line between abnormal and monstrous.

From the opposite end of the stage, behind the curtain on stage right, Nicoleta nods at me. I reach for the rope and yank down. The pulley spins and whistles, and the curtain rises.

Nicoleta struts—a very practiced, rigid strut—into the spotlight, her heels clicking and the slit in her gown revealing a lacy violet garter at the curve of her thigh. When I first created her three years ago, she had knee-shaking stage fright, and I needed to control her during the show like a puppet. Now she’s so accustomed to her role that I turn away, unneeded, and tie on my best mask. Rhinestones of varying sizes and shades of red cover it, from the curled edges near my temples to the tip of my nose. I need to dazzle, after all.

“Welcome to the Gomorrah Festival Freak Show,” Nicoleta says.

The audience gawks at her. Like the particular Up-Mountainers in this city, and unlike any of the other members of my family, Nicoleta has fair skin. Freckles. Pale brown hair draped to her elbows. Skinny wrists and skinnier, child-like legs. Many members of Gomorrah have Up-Mountain heritage, whether obvious or diluted, but these northern city dwellers always expect the enticingly unfamiliar: sensual, audacious and wild.

The audience’s expressions seem to say, Poor, lost girl, what are you doing working a

t Gomorrah? Where are your parents? Your chaperone? You can’t be more than twenty-two.

“I am Nicoleta, the show’s manager, and I hope you’re enjoying your first Gomorrah Festival in...three years, I hear?”

The audience stiffens; they stop fanning themselves, stop chewing their candied pineapple. I curse under my breath.

Nicoleta has a knack—a compulsion, really—for saying the wrong thing. This is the Festival’s first night in Frice, a city-state known—like many others—for its strict religious leaders and disapproval of the Gomorrah lifestyle. Three years ago, a minor rebellion in the Vurundi kingdom ousted the Frician merchants from power there. Despite quickly reclaiming its tyrannous governorships, and despite Gomorrah’s utter lack of involvement, Frice decided to restrict the Festival’s traveling in this region. I can’t have Nicoleta scaring away our few visitors by reminding them that their city officials disapprove of them being here, even at an attraction as innocent as a freak show.

“For those of you with weaker constitutions, I suggest you exit before our opening act,” Nicoleta says. Her tone rises and falls at the proper moments. The theatrics of her performance in our show are the opposite of Nicoleta’s role in our family, which Unu and Du have dubbed “stick in the bum.” Every night, she manages to transform—or, better put, improve—her entire demeanor for the sake of the show, since her own abilities are too unreliable to deserve an act. Some days, she can pull our caravans better than our two horses combined. Others, she needs Tree to open our jars of lychee preserves.

“The sights you are about to witness are shocking, even monstrous,” she continues. A young boy in the front row clings to his mother, pulling at her puffed, apricot sleeves. “Children, cover your eyes. Parents, beware. Because the show is about to begin.”

While the audience leans forward in their seats, I prepare for the upcoming act by picturing the Strings, as I call them. I have almost two hundred Strings, glowing silver, dragging behind me as I walk, like the train of a fraying gown. Only I can see them and, even then, only when I focus. I mentally reach down and pluck out four particular Strings and circle them around my hands until they’re taut. The others remain in a heap on the wooden floor.

“I’d like to introduce you to a man found within the faraway Forest of Ruins,” Nicoleta lies. Backstage, Hawk stops playing the fiddle, and Unu and Du reduce the tempo on their drums. I yank on the Strings to command my puppet.

Thump. Thump.

The audience gasps as the Human Tree stomps onto the stage. His skin is made entirely of bark, and his midsection measures as wide as a hundred-year-old oak trunk. It’s difficult to make out his facial features in the twisted lumps of wood, except for his sunken, beetle-black eyes and emptiness of expression. Leaves droop from the branches jutting out from his shoulders, adding several feet to his already daunting stature. His fingers curl into splintery twigs as he waves hello.

From backstage, my hand waves, as well. If I don’t control Tree, he’ll scream profanity that will make half these fancy ladies faint. If he works himself into a real tantrum, he’ll tear off the bark on his stomach until blood trickles out like sap.

His act begins, which is mostly him stomping around and grunting, and me yanking this way and that on his Strings to make him do so. I crafted him when I was three years old, before I considered the performance potential of my illusions.

The six other illusions wait with me backstage.

Venera, the boneless acrobat more flexible than a dripping egg yolk, brushes rouge on her painted white cheeks at a vanity. She pouts in the mirror and then pushes aside a strand of dark hair from her face. She’s beautiful, especially in her skintight, black-and-purple-striped suit. Every night, the audience practically drools over her...until they watch her body flatten into a puddle or her arms roll up like a croissant.

Beside her, Crown files the fingernails that grow from his body where hair should be. He keeps the nails on his arms and legs smooth, giving him a scaly look, but he doesn’t touch the ones on his hands and head, which are curled, yellow daggers as long as butcher knives. Though Crown was my second illusion, made ten years ago, he appears to be seventy-five. He always smokes a cigar before his performance so his gentle voice will sound as prickly as his skin.

Hawk plays the fiddle in an almost spiritual concentration while what’s left of a chipmunk—dinner—hangs out of her mouth. Her brown wings are tucked under her fuchsia cape, where they will remain until she unfolds them during her act, screeches and flies over the—usually shrieking—audience. Her talons pluck at the fiddle’s strings at an incomparable speed. Her ultimate goal is to challenge the devil himself to a fiddle contest, and she figures by traveling with the world’s most famous festival of depravity, she’s bound to run into him one day.

Blister, the chubby one-year-old, plays with the beads dangling off of Unu and Du’s drum. Rather than focusing on their rhythm, Unu and Du bicker about something, per usual. Du punches Unu with their shared left arm. Unu hisses an unpleasant word loudly, which Blister then tries out for himself, missing the double s sound and saying something resembling a-owl.

Gill snaps at them all to be quiet and then resumes reading his novel. Even wearing a rusted diver’s helmet full of water, he manages to make out the words on the pages. Bubbles seep from the gills on his cheeks as he sighs. As the loner of our family, he generally prefers the quiet company of books to our boisterous, pre-show jitters. He only raises his voice during our games of lucky coins—he holds the family record for the most consecutive wins (twenty-one). I suspect he’s been cheating by allowing Hawk, Unu and Du to forfeit games on purpose in exchange for lighter homework assignments.

“Keep an eye on Blister,” I remind the boys. “Those drums are flammable.”

“Tell Unu to stuff a drumstick up his—” Du glances hesitantly at Gill “—backside.”

“That’s your backside, too, dung-brain,” Unu says.

“It’s an expression,” says Du. “I like its sentiment.”

It would hardly be a classic Gomorrah Festival Freak Show if the audience couldn’t hear my brothers tormenting each other backstage.

“I’ll stick it up both your assholes if you don’t shut it,” I say. They pay me no attention; they know I never follow through with my threats.

“A-owl,” Blister says again.

“Language, Sorina,” Gill groans.

“Shit. Sorry,” I reply, but I’m only mildly chagrined. Blister’s been hearing all our foul mouths since the day he came to be.

One by one, they perform their acts: the Boneless Acrobat; the Fingernail Mace; the Half Girl, Half Hawk; the Fire-Breathing Baby; the Two-Headed Boy; and the Trout Man. The audience roars as Hawk screeches and soars over their seats, cheers at each splash of Gill flipping in and out of his tank like a trained dolphin. They are utterly unaware that the “freaks” are actually my illusions, projected for anyone to see.

The only real freak in Gomorrah is me.

“For the finale,” Nicoleta says, as I hurriedly smooth down my shoulder-length black hair, “a mysterious performer who’s been with Gomorrah since her childhood. She’s the Girl Who Sees Without Eyes, and if you remain in your seats, she’ll reveal wonders you can see, hear, smell and even touch.”

I greet the audience as Unu and Du wheel Gill’s massive glass tank offstage. The hem of my black robes swish across the floor, and a hood drapes over all but my violet-painted lips. Count Pomp-di-pomp murmurs to the plump woman beside him, perhaps his wife. Another person Jiafu will need to sneak around during my act.

The room holds its breath as I remove the hood, only to reveal my mask.

“Take the mask off,” a man shouts from the back.

“Those who see her true face turn to stone,” says Nicoleta. Of course, that’s horseshit. I just hate the screams, same as Tree with his bark skin, Unu and Du wi

th their two heads and Hawk with her wings and claws. As good as we have it in Gomorrah, no one wants to be a freak.

The fiddle and drums fade to silence as I raise my arms.

The tent’s ceiling and grass floor disappear, replaced with colorful galaxies so the crowd seems suspended within the cosmos. The woman beside Count Pomp-di-pomp shrieks and lifts her feet off the endless, black ground and then wipes the sweat from her forehead with her pearl-studded glove.

Nicoleta jabbers a spiel about the wonders of my sight, as if my lack of eyes allows me to see more than everyone else. Between my forehead and cheekbones is flat skin, but I can see just the same as the rest of the world. I’m an illusion-worker, the rarest form of jynx-worker, gifted in mirages real enough to touch, smell, hear and taste. My most intricate illusions are my family and the other members of the freak show: living figments of my imagination.

I’ve never met another illusion-worker—only read about them—but as far as I know, I am the only one born without eyes who relies on my jynx-work to see. No doctor or medicine man can explain how this works. Maybe I don’t see like everyone else does—it’s not as if I could test that out—but I see, color and all, and I’m not one to question things I don’t really need answers for.

I throw all of my energy into this performance, so much that my Strings are fully visible to me and tangle at my feet. I avoid moving around onstage, in case I trip. Normally, the Strings aren’t solid, but when I’m commanding this much power? My ankle just might catch, and I’ll topple into the front row.

Fabricated constellations whirl past, and the audience grips the edges of their seats. The planets orbit the room as if the tent marks the center of the universe and that universe is performing for us, its revolutions a celestial dance and me, the musician.

During my ten-minute act of shooting stars, crescent moons and burning suns, I’m too consumed by the exertion of my performance to notice if Jiafu stole Count Pomp-di-pomp’s ring. The illusion dissipates, and I lower my hands. I stare around the tent with exhilaration, and my chest heaves up and down beneath my thick robes. I was marvelous.

King of Fools

King of Fools Ace of Shades (The Shadow Game Series)

Ace of Shades (The Shadow Game Series) King Of Fools (The Shadow Game series, Book 2)

King Of Fools (The Shadow Game series, Book 2) Ace of Shades_The Shadow Game Series

Ace of Shades_The Shadow Game Series Daughter of the Burning City

Daughter of the Burning City