- Home

- Amanda Foody

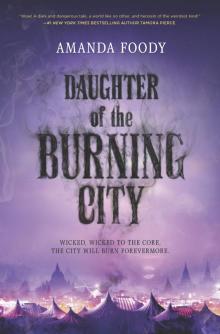

Daughter of the Burning City Page 3

Daughter of the Burning City Read online

Page 3

Gomorrah is chaos.

CHAPTER TWO

The coin merchant’s table crashes to the ground, and lucky coins cascade onto the grass in a rushing clatter. The official whose horse overturned the stand stops and dismounts. I hold my breath and squirm closer to Gill as the merchant drops to his knees and collects his fallen merchandise.

“We need to hurry,” Nicoleta says. She points in the direction of a nearby path for us to flee.

The official picks up a coin and examines it. “The Harbinger? He looks like a demon.” He throws the coin into the merchant’s lap. “Are you a jynx-worker?”

“No,” the merchant says, his voice strong. He stands to meet the official’s eyes.

“Then what are these for, if not divining?”

“It’s a game. Collector’s items.”

“A game,” he mocks. “A festival. Pretty words for a city of rot and smoke. Nothing about this place is play.”

Gill tugs on my arm. The others have broken apart and are running for Nicoleta’s path. “It’s time to go,” he says.

I eye the ticket booth behind us, loath to lose all the money we spent. We saved for this night. I won’t let a few Up-Mountain officials force us to throw our money away and terrorize us in our own home.

I disentangle myself from Gill’s grip. “I’m getting our money back.”

Gill’s eyes widen in alarm. “There are more important things.”

“No. Family night is a whole month of saving, and we didn’t get to have it. I’m getting. Our money. Back.” I say this sternly enough so that Gill won’t argue with me. And he doesn’t.

“Be careful,” he says.

“Always am.”

I whip around toward the ticket booth. A crowd surrounds it, shouting at the girl inside, who’s shouting right back. There are twenty yards between them and me, plus a few officials in their white coats on whiter stallions beneath the Menagerie’s banners, admiring the chaos around them and tormenting those in costume, searching for jynx-workers.

Villiam always told me the Up-Mountains hate us because they are afraid. He’s told me stories that date back two thousand years, when Gomorrah was once a true city in the Great Mountains—a narrow strip of land dividing the two continents. When its skyline was blue instead of burning. When jynx-workers wielding fire and shadow could dominate regions at any end of the world. Even though anyone can be born with jynx-work in their blood, it was the Up-Mountainers who turned away from it, and the Down-Mountainers who came to celebrate it. The Up-Mountains—from the wintry tundras in the north, to the humid bayous in the south, across cultures, across peoples—united under their common-held fear and warrior god. Now they are powerful, and even the most capable jynx-worker is no match for the massive Up-Mountain armies.

It will only take a few minutes to retrieve the money, I tell myself. Screams ring out behind me. Figures appear and disappear in the constant Gomorrah smoke. Hooves thunder past.

I’ll be home in a few minutes. Like hell I’m leaving without our money. I am the proprietor’s daughter, and I will never be afraid while within Gomorrah.

My illusion-work is not entirely for entertainment. A useful trick I’ve learned while living in the Festival is to convince someone they are looking at one thing, when really they are looking at something else. A sleight of hand, of sorts. It’s significantly easier than persuading someone there’s nothing to see at all.

I cast my usual trick: a moth.

To those around me, there is no girl passing them in a long cloak. There is no person. No shadow, even. There’s a moth, fluttering from torch to torch in lazy curls, oblivious to the hysteria around it. A torn scrap of paper drifting in Gomorrah’s smoke. If they concentrated or stood at a distance, they would glimpse the outline of my body, blurry like a reflection in a pond. But no one is going to stare that closely at a moth.

With my illusion protecting me, I pass the officials without notice and head to the booth. I shelter behind a tentpole, blocking myself from the view of those in the clearing. Once the illusion fades, I don’t want an official to harass me because of my eyeless mask. Or worse, for someone from Gomorrah to recognize me as the proprietor’s daughter and demand I stop the officials. As if they’d listen to a sixteen-year-old, small Down-Mountain girl. A jynx-worker. A freak.

I let go of my illusion and push my way to the front of the those crowded around the ticket booth. Inside, the frazzled girl shrieks, “You all live here! Just come back tomorrow!” Somewhere to our right, another vendor stand is knocked to the ground with a crash, followed by the thudding of wooden jugs of spiced wine.

She’s right. Everyone in the group has mixed features and wears Gomorrah trousers and tunics. Those in Gomorrah are known for their stinginess, and waiting a whole day for our money back isn’t going to cut it—not for me, not for anyone here. Those tickets cost a fortune.

A child screeches. I briefly look away from the booth, but it is an Up-Mountain child. He has nothing to fear. His father shushes him and pulls him away from the frenzied horses.

Be careful, Gill told me.

I’m definitely not being careful.

“Today you say money back, tomorrow you’ll change your minds,” one man says. He holds out his grubby hand beneath the glass opening of the booth.

“Where’s the manager?” another asks.

“He’s calming the swan dragon,” the girl snaps. Her eyes fall on me, in the fringe of the crowd, and they widen. “You’re Villiam’s daughter.” The others turn to me, and I curse under my breath. They all recognize me, but I know none of them. I shouldn’t be here. “Take care of them. The Menagerie has to focus on its animals and the safety of the Gomorrah patrons and residents first. If you all return first thing tomorrow, we’ll refund your tickets.”

She scampers away from the booth, leaving me with the unruly group. She was smart. The Menagerie, being Gomorrah’s most profitable attraction, receives Villiam’s special attention. Right now, I should care more about their needs than those of a few residents. That is what a proprietor would do. A proprietor would have their priorities straight.

The group watches me expectantly. A proprietor would also know at least a few of their names, and I can barely remember the names and faces of the neighbors I’ve had for eight or more years. But they all know mine. My face is the most recognizable in the Festival. I do not search for anonymity, but I hate to glimpse the repulsion or pity in their eyes.

“It’s for your safety,” I stammer. “The swan dragon—”

“—is older than shit,” one woman says. “Lot of harm she’ll do.”

“Let me take your names. I’ll make right sure the Menagerie returns your money tomorrow—”

“With all the officials here, wreaking havoc? You’ll be too busy cleaning up their mess, and you won’t bother with this.” The man spits at my feet. I grimace. He would hardly do that to Villiam, or even Villiam’s assistant, Agni. It’s easier to dismiss a freak. And truth be told, Villiam rarely assigns me any real work. My proprietorship lessons are lectures of micro-agriculture and craftsmanship; about the external structure of Gomorrah, a vast, traveling city. Never about what truly makes it tick.

“To hell with this.” The man storms off.

Fine, let him leave. He’ll probably rant about how lousy I am to his friends, which will return to me in whispers and stares—never anything outright rude, nothing that might risk inciting Villiam’s wrath, but the kind that makes me feel like a freak show even outside the performance tent.

I stare at the small, copper coins in the tin box inside the booth—dull and tarnished but still more beckoning than starlight. It doesn’t matter that I don’t know these people’s names. I know why they’re here, same as me. For their month’s earnings. For the money to make sure no one in their families has to do work on

the side, like petty thievery. To ensure their loved ones have whatever they need, like medicine.

“Just need some paper,” I mutter and then slip inside the ticket booth. I grab a sheet and a pencil. “I’ll take your names—”

“But how will we—”

“I want my money back as much as you do. Now give me your damned names so that we can all get the hell out of here.”

The woman in front huffs. “You’re crass for a princess.”

I hate that nickname. Real princesses are no more than pretty bargaining chips. I’m no pawn, and I gave up on pretty a long time ago.

“Not for Gomorrah’s princess,” I say.

They stop bickering, give me their names and shuffle away. Once I’m alone, I reach beneath the counter and grab my family’s forty-five copper coins. Then I slap the list of names on the table—no longer my problem—and leave.

Frice has stormed the Festival. Gomorrah has bigger things to worry about than ticket refunds.

My trusty moth illusion gets me safely from the Menagerie to our neighborhood, though I pass several officials along the path and cringe away each time. But they cannot see me, and if I concentrate hard enough, they could touch me and not know it. I stumble toward our tent, sweaty and out of breath but victorious.

Gill waits outside, and I brace myself for the scolding that I probably deserve. He swats at my moth until I drop the illusion. “Are you all right?” he asks.

“I’m fine.”

“That was rash,” he says. “You could’ve been hurt.”

I jingle my pocket. “Got the money.”

“No one cares about the money. We were all worried sick.”

I know it wasn’t the smartest plan. But tomorrow night, when the officials leave and Gomorrah has cleaned itself up, everyone will be thankful for the extra change.

“Well, I’m fine.” I push past him to go inside, but he grabs my arm.

“And why was Jiafu here tonight?” he asks, for the second time.

“How should I know? Maybe he wanted to watch our show,” I say, careful not to let the others overhear inside. Crown and Nicoleta also don’t approve of my thieving with Jiafu, and some of them—like Hawk and Unu and Du—don’t even know about it.

“Jiafu is trouble, Sorina.”

“It was nothing. All’s dandy.” Jiafu and I have swindled enough jobs at the show to know it never affects our ticket sales.

“I don’t know what you two did,” he says, “but Gomorrah’s in enough trouble here as it is. If rumors spread beyond Frice that we’ve been stealing from patrons, then the other Up-Mountain cities will revoke their invitations to come. Not to mention all this chaos.”

He acts as if Jiafu and I are the only thieves in this whole festival of debauchery. To the visitors, the chance of pickpockets or magical mischief accounts for half the thrill of Gomorrah.

“It was a small job. Count Pomp-di-pomp is supposed to be a bit dim, anyway. He’ll probably think he lost his ring himself.”

Gill rolls his eyes. “It’s Count Pompdidorra. He’s a very influential man.”

“Whatever.”

“Sorina,” he says, sighing. Most of Gill’s sentences are followed by a sigh. At least half of those are aimed at me. When I created Gill, I had “loving uncle” in mind, but, instead, he’s more of a nuisance. Though maybe that’s a bit harsh. It’s not that I don’t love Gill. Not that he doesn’t love me and all of us. But he’s certainly grumpier than in my original blueprints. If we wanted to live by all his rules, we’d go live in a religion-crazed Up-Mountain city. The only person who listens to Gill is

Nicoleta, who is essentially his henchman, repeating his advice or scolding someone whenever Gill isn’t present to do so himself.

“To be frank—” Gill is always frank “—you’re jeopardizing the already grim reputation of the entire Festival. And if people keep losing valuable possessions during our show, no one’s going to buy tickets.”

I’m done with this conversation. Unless Gill can concoct a new idea for me to earn some coin for Kahina, then I’ll stick with Jiafu. I’m not really hurting anyone. The patrons we select are too rich to notice a missing necklace here, a missing watch there.

“It’s my show,” I say.

“If it’s all your show, you can do tricks in this tank next time. Or fit into Venera’s two-by-two-foot box,” he snaps. “Don’t be a child.”

“Technically, I’m older than you,” I say. I created Gill when I was nine, which only makes him seven years old.

He sighs. “Of course, Sorina, you always have the last word.”

This particular statement infuriates me more than anything else. I’m sorry I worried him, but Kahina is more important than the slim risk involved. And I don’t understand how I could possibly be damaging the Festival’s reputation when people are always whispering about assassins and drug dealers in the Downhill. Petty theft is nothing compared to that.

I turn, my cloak swishing behind me, and stomp inside.

The others sit around our foldout table, huddled together on floor cushions. By the untouched game of lucky coins and the way they fidget, I can tell they’ve been worried.

I toss the forty-five coins on the table, which spill out of their pouch with clatters and clangs. Venera grimly gathers them up to add to our family-stash jar. “Got them no problem,” I say, knowing that I sound like an ass.

“It’s almost midnight,” Nicoleta says. “You took a long time.”

“Is it?” Jiafu and I usually meet at midnight after jobs, but I didn’t notice him waiting for me outside. I hate to leave them again, if only for a moment, but I need to talk to Jiafu.

“We can play lucky coins, now that we’re all here,” Unu says. He holds up the Beheaded Dame coin—the jewel of his collection—to glint in the lantern light.

“I’m not ready to lose again just yet,” I say. “I’m going to keep watch and make sure no officials come near the tent. I’ll be—”

“You shouldn’t go outside,” Nicoleta says, sighing. If one more person sighs at me, I’ll tear my hair out. The bald girl who sees without eyes. What a sight.

“—just out back,” I finish, waving and slipping out before any of them can stop me. There’s less commotion in our neighborhood than near the Menagerie and Skull Gate. Plus, I have my illusions to obscure me. I’m not worried.

The night air is sticky, yet refreshing compared to the tension with the others inside. Thankfully, Gill has disappeared—skulked back to his tent, where he’ll probably keep to himself the rest of the night, reading another one of his boring novels, where nothing exciting or romantic ever happens, and the reader always learns some righteous lesson in the end.

Lightning bugs blink within clouds of gnats, circling my face. The smoke that envelops Gomorrah utterly blocks out any view of the sky. The smoke is part of Gomorrah’s legend: once upon a time, we were burned to the ground. But we did not die. Instead we kept burning, kept moving, kept growing. The smoke surrounds us, even if we no longer burn. There is no fire, but sometimes, if you catch yourself around Gomorrah’s edges, the air thickens from stifling heat and the lanterns glow a little bit brighter. It reminds me of walking into the city’s memory—a very ancient memory.

This section of Gomorrah is lit by white torchlights and paper lanterns, which wear golden halos in the gray fog. Everyone in the Festival seems like a silhouette, a shadow of an actual person. It makes it easy to get lost and, depending where you are in Gomorrah, never be found again.

I scan the area beside my tent—a small clearing that serves as the back of two other tents, which house a family of fortune-workers and a silk salesman. Jiafu is nowhere. We usually meet outside after jobs, so why isn’t he here? If he’s skipping out on me, I swear, he’ll wake up tomorrow thinking there are dung beetles crawlin

g out of his nostrils. I have a hard time believing Jiafu, the master of all crooks, would be scared of a few officials.

I sit on the grass, facing toward the thousands of tents that make up the Gomorrah Festival, the tallest being the Menagerie at the center. The family-friendly attractions—if you could call anything at Gomorrah family-friendly—are closest to the entrance, like games, circuses and my freak show. The majority of the Festival is in the back—private tents for prettymen and prettywomen, bars and gambling. We call that area the Downhill. Of the thousands of people who live in Gomorrah, I know the fewest from there.

Jiafu has five minutes before I get angry.

To the left, something catches my eye. A golden centipede wriggles down a tent post, and I suck in my breath and examine it. It’s the size of my pinky but twice as wide, with beady black eyes and soft fuzz. I gently pick it up and let it tickle my palm with its hundred feet.

I don’t remember when my bug collection began. I have over three hundred insects, gathered from various regions where the Festival has taken me, both in the Up-Mountains and Down-Mountains. A charm-worker down the way preserves them for me in glass vials, which I keep for decoration in my room—both for the aesthetics and to ensure that Nicoleta rarely comes in to nag me. Occasionally Villiam will gift me a book of local insects so I can learn about the ones in my collection. I like to consider myself an expert on all creepy crawlies. Probably because they make other people uncomfortable, but I see just how unique and fascinating they are. Highly underrated creatures. The bugs and I have this in common.

A horn blares across Gomorrah. Followed by screams.

“What the hell is that?” I wonder aloud. The centipede crawls up my wrist and arm, unperturbed. It sounded like a city horn from Frice. Maybe the officials are leaving.

I tiptoe around our three tents—the two where we sleep, and the Freak Show’s tent—wishing I wasn’t alone, in case I do need to face an official. Wishing we, like most of Gomorrah’s residents, lived near the Festival’s perimeter, not along a main path.

King of Fools

King of Fools Ace of Shades (The Shadow Game Series)

Ace of Shades (The Shadow Game Series) King Of Fools (The Shadow Game series, Book 2)

King Of Fools (The Shadow Game series, Book 2) Ace of Shades_The Shadow Game Series

Ace of Shades_The Shadow Game Series Daughter of the Burning City

Daughter of the Burning City